visit to boston

I spent a long weekend in Boston recently, staying in Back Bay—an area I was eager to revisit, having lived there back in 2016. As with everywhere I visited, not much had changed, but if you looked long enough, you could spot the differences. A shop or two might be different. Or the odd building that I definitely didn’t recognize.

While I was there, I visited the MIT Museum, which I had never been to before. It recently relocated to Kendall Square, which is looking very sleek and modern–no longer the construction site I remember from my time there. The museum is impressive, and they have a wide variety of exhibits describing some of MIT’s contributions to various fields. I sat for a bit in a room with artistic depictions of some possible outcomes of geoengineering, feeling that odd mix of excitement and dread one feels when pondering too long on that cyberpunk future. I saw some backup components of the original Apollo Guidance Computer and admired an impressive collection of gadgets from throughout the last century.

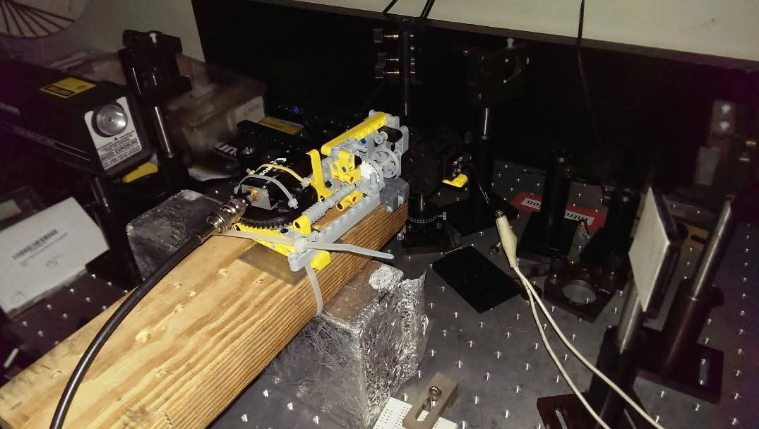

One particularly interesting thing for me was a display dedicated to Lego Mindstorms. I will always remember the Mindstorms set very fondly–it was the original gateway for me into a career in technology. The set was my introduction to programming and engineering concepts like sensing and feedback. I can trace a clear through line from that point to high school lab experiments to graduate research to now.

One of the key figures in early development of Mindstorms was the MIT professor Seymour Papert, who wanted to use Lego as a way of enabling children to make machines that ran with the Logo programming language that he had developed. Papert was an advocate of an educational theory known as Constructionism. This theory emphasizes the importance of learning through guided discovery, using what one has already learned in order to build new knowledge. Papert captured these ideas in a book titled Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas (available online via ACM Digital Library), which is where the Lego product got its name.

I’ve always thought of Lego, and especially Mindstorms, as one of the key pieces in my approach to learning. I’m a tactile learner; I don’t ever understand as well as I do when I can feel how something works. Lego always appealed to me for this hands-on element, but it also fascinated me with its presentation of process. The instructions lay out precisely where, what, and how much to add, step-by-step, allowing you to methodically create the end result. Seeing the way that motors, sensors, and programmatic control could be added to these creations, I could understand the method by which even more complicated things were created. Even when I didn’t understand the technology around me, I understood the process. The key was to learn to build pieces of the big and impossible thing. Build enough pieces, and you eventually grasp the whole thing.

And it occurs to me, as I’m researching the history of Mindstorms and the educational philosophy behind it: this was the plan all along. I was one of the beneficiaries of that new wave of teaching that came about in the 80’s. It seems to me that it has come full circle in a way. Not only has this influence helped make me into a scientist, it has made me realize the importance of this style of teaching and learning. I realize that I’m a member of the Mindstorms generation. Not just a learner, but a builder and a tinkerer; dedicated to showing others how to do the same.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: